Force-renew the DHCP lease on your Mac.

DHCP is a networking protocol used to assign an IP address to your Apple device. Here’s how to force a new IP address on macOS.

Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP) allows a network device to request an IP address from a DHCP server on a network. DHCP makes starting and configuring computers easier since it’s usually automatic and doesn’t require any user intervention.

There are separate versions of the DHCP protocol for IP4 and IP6 (DHCPv6).

In most cases, DHCP servers run either on your home network (on your router), on your ISP’s network, or on corporate servers in business settings. DHCP can also be hosted in the cloud.

Part of the benefit of using DHCP is your client machine doesn’t have to know the address of the DHCP server – discovery is automatic and transparent (and is based on UDP actually). Client machines can keep searching for DHCP servers on a network until they find one that can provide an IP address.

You can also run your own standalone DHCP servers at home, but unless you’re familiar with the intricacies of the protocol and networking it might be more trouble than it’s worth: misconfiguration of a local DHCP server can cause your network to behave erratically.

Most modern home routers, cable, and fiber-optic modems handle DHCP for you.

The main idea behind using DHCP is that computers can dynamically and automatically make an internet connection without each machine having to be manually configured with an IP address.

The time a DHCP server allows a single machine to be connected to one IP address is called the Lease Time. Default lease times are usually twenty-four houses, but can vary. When the lease time expires, either a new IP address is assigned, or the same IP address is used with the lease time reset.

Lease times are used so that if devices disconnect from the network, their IP addresses can be recycled and assigned to other devices on the network.

DHCP History

DHCP’s predecessors were RARP and BOOTP – both defined in the early 1980’s. When the internet began to become commercialized in the early 1990’s it quickly became obvious that static IP management for huge numbers of IP devices was impractical.

Based on BOOTP, DHCP includes the noticeable differences of IP address pool allocation and reuse, and platform-specific configuration settings per connected machine.

The final original version of DHCP was later updated in 1997 with a few additional small changes, and DHCPv6 was first defined in 2003 (and later updated in 2018).

DHCP startup on Macs

When you start your Mac, a background process goes through the list of its active network interfaces in the order listed in System Settings->Network and pings your network for DHCP servers (by broadcasting the DHCPDISCOVER message) to request an IP address for each active interface in the list (unless a specific interface is set to use manual IP addressing).

If any DHCP servers are listening and responding to this request (with a DHCPOFFER message), your Mac will ask one of them for an IP address for each network interface. The responding DHCP server creates a new internal IP address in a table – and then sends it to your Mac for its use.

macOS will take each received IP address and connect an active network interface to it. These addresses aren’t “real” – they’re actually mapped internally at your router or ISP to an external address on the internet.

A typical address your Mac might receive from a DHCP server might look something like “192.168.0.1”.

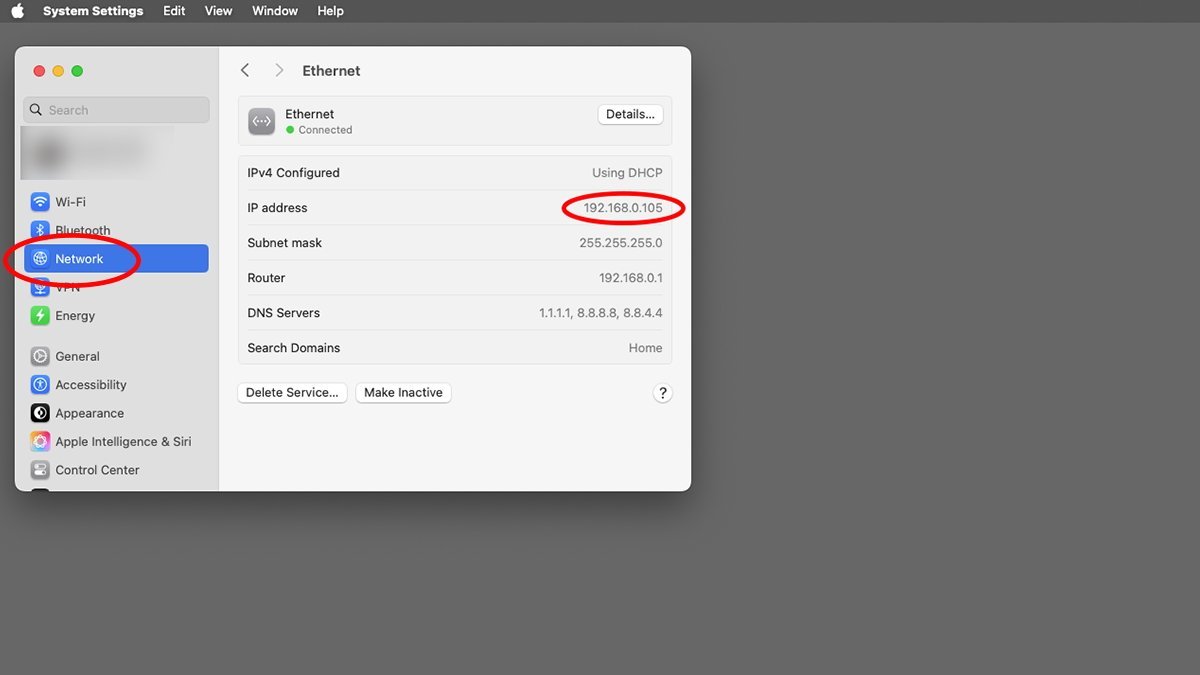

If you go to System Settings->Network and click on an active network interface you’ll see a list of the network settings for that device. For example, Ethernet:

System Settings Network pane in macOS.

The device pane displays whether the device is active, its IP address, the subnet mask used, and the local router address. In the case of a home network, the router address will most likely be your broadband modem, or a local router if you have one configured.

The device info also displays which DNS servers you’re using, and how your internet connection is configured. In the case of DHCP, it will be displayed at the top.

If you’re on a network that doesn’t use DHCP but uses static IP addresses for each device instead, this line will read “Manually” instead of “DHCP”.

Once your Mac has requested and obtained a DHCP address from a server, these values will all be filled in automatically.

Requesting a new DHCP IP address

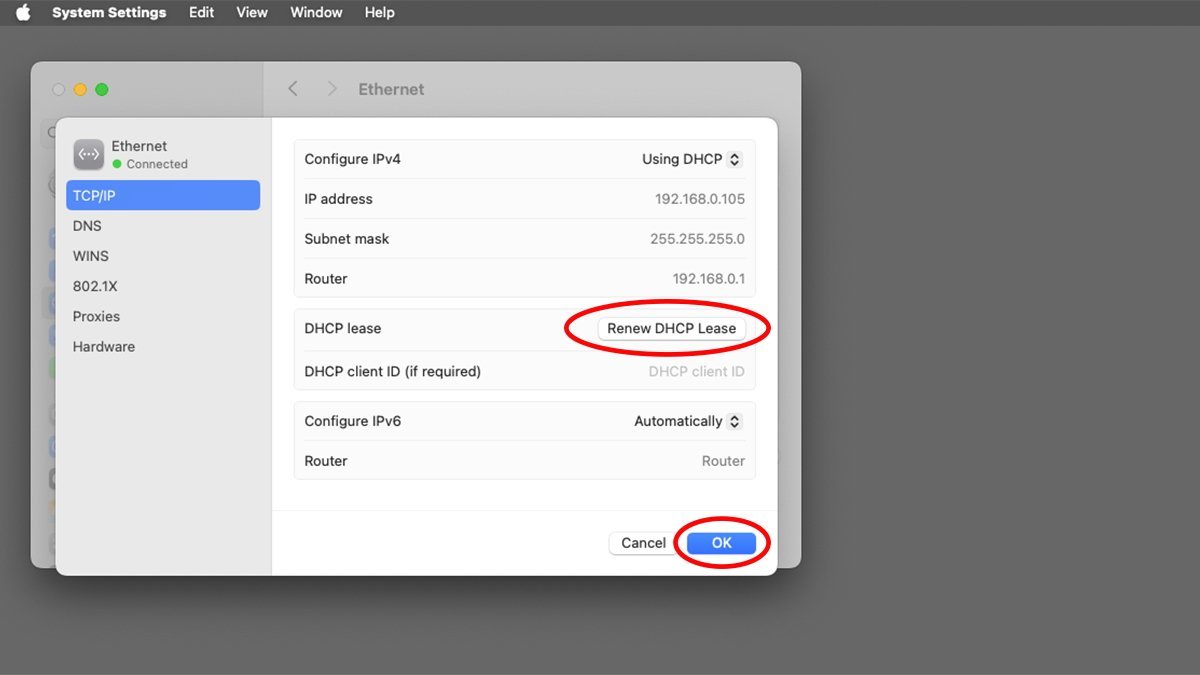

If for some reason you want to request a new IP address from your network’s DHCP server, click the Details… button at the top of the device info pane. You’ll see a sheet listing network and hardware specifics for that device.

One of the items in the sheet’s list is TCP/IP. If you click TCP/IP, you’ll essentially see the same info as in the device pane, but you’ll also notice a Renew DHCP Lease button:

Click “Renew DHCP Lease” to reset the IP lease on your Mac’s network interface.

Clicking this button will send a request to the DHCP server to reset the DHCP Lease Time – or, in some cases request a new IP address. After clicking the button you’ll need to wait a few seconds for the request/response from the server. When the new lease/address is received, macOS will update the info in the device interface pane automatically.

If you’re using a VPN app (and it’s connected) you may also need to disconnect and reconnect it once you obtain a new IP lease for your Mac.

But why?

You may be wondering why you would want to manually renew your DHCP lease. The answer is: usually you don’t. The only time you need to do this is when you’re experiencing networking conflicts or problems – for example, if your machine went to sleep and some other device on your local network is now using the IP address you were previously using.

Or in some cases if intermediate local routers or switches have changed on your network and your Mac didn’t know about it – or as mentioned above in the case of VPN changes (some routers can contain DHCP relay agents which talk to DHCP servers).

In the event your Mac says its network interface is connected but you don’t have connectivity, you can try clicking Renew DHCP Lease to see if it solves the problem.

DHCP makes our lives vastly easier by doing away with manual IP address configuration which can quickly become a burden on large networks. DHCP is easy and automatic and most of the time you won’t even need to think about it.