The first Apple Silicon chip used in a Mac, the M1, implements Apple’s first custom controller for USB4 and Thunderbolt 3 and delivers the platform’s first systems meeting the new USB4 specification. Notably, Apple has brought USB4 to market about a month after Intel’s own 11th Gen Tiger Lake processors for PC notebooks.

Apple Silicon’s first with USB4 is a sign of things to come

[Note: the original version of this article incorrectly stated that Apple had brought USB4 to market ahead of Intel; a correction by Ryan Smith of AnandTech noted that some PCs have already shipped with Intel’s TL chips. Smith stated that Dell began delivery of systems supporting USB4 in the first week of October.]

M1’s support for USB4 isn’t exactly an earthshaking leap on the same level as Apple’s custom GPU, Neural Engine, or the Unified Memory Architecture of its new M1 System on a Chip. But it is noteworthy that Apple has been able to quickly implement and deliver a new emerging standard on its own custom Apple Silicon— a rapidly expanding advantage the Mac maker now holds over Windows PC and Android licensees.

The USB4 specification is largely an attempt to simplify and streamline the confusing array of definitions related to USB 3.x and other protocols that can work over USB-C cables, including HDMI and DisplayPort.

USB4 also represents the shift of Intel’s proprietary Thunderbolt protocol from a paid licensing scheme that required an Intel controller chip to an openly licensed standard now under the control of the USB standards body. In fact, most of the technical improvement in USB4 is effectively a copy of Thunderbolt 3’s high-speed connectivity features, now available from the nonprofit group that promotes USB as an industry standard.

Apple’s ability to develop its own custom controller supplying Thunderbolt 3 speed and compatibility, right on the M1, comes directly from Intel’s move to share the technology as part of USB4. The fact that Apple’s M1 hit the market in a 5nm chip before Intel is eye-opening.

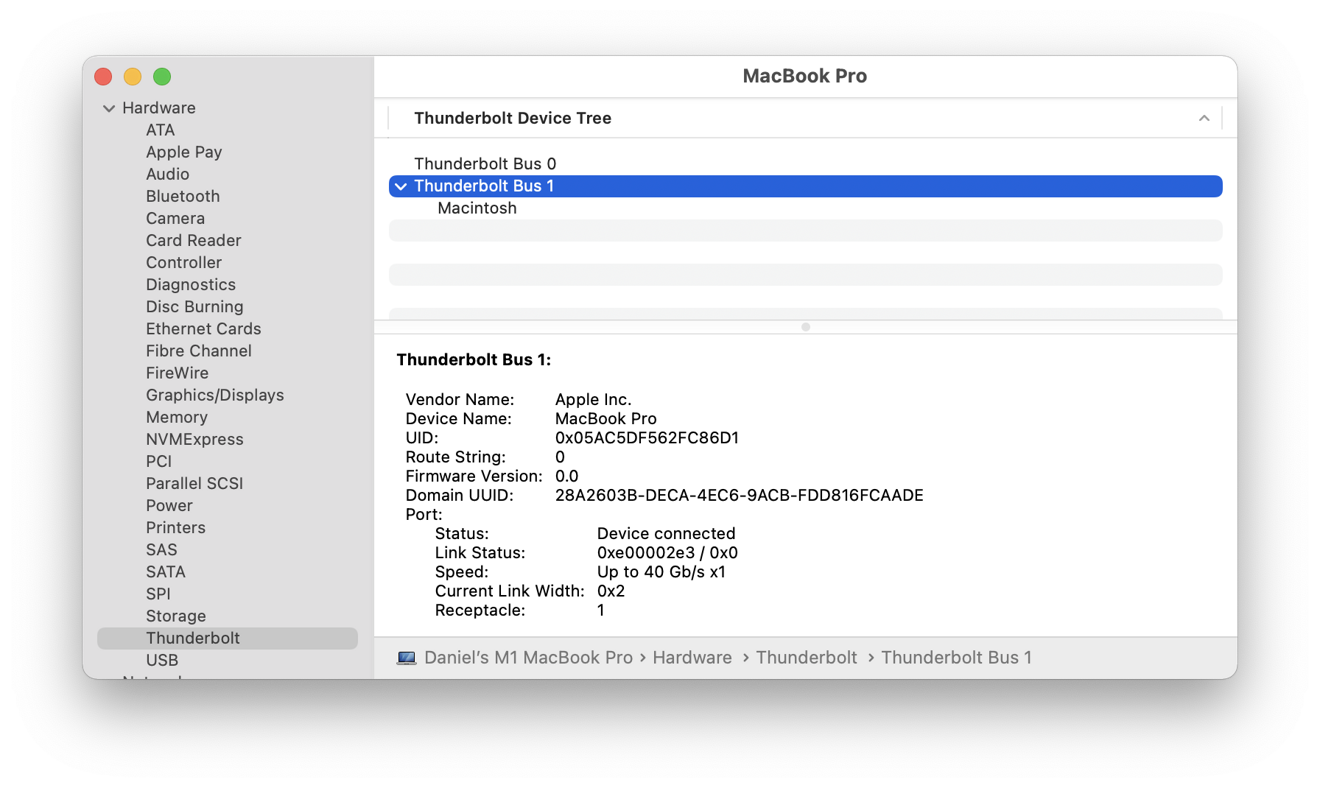

M1 MacBook Pro connected via 40Gbps Thunderbolt 3 to an Intel Mac in Target Disk Mode

Thunderbolt was initially developed by Intel in partnership with Apple, originally under the name “Light Peak.” It was intended to be a modern, optical replacement for FireWire— a standard Apple had developed on its own in the early 90s but failed to gain broad PC industry adoption.

But a decade later, Intel’s Thunderbolt has seemingly suffered the same fate as FireWire: enthusiastic adoption by Apple on its Macs but with limited penetration on generic PCs with less appetite for pushing state of the art. Adoption of Thunderbolt has mostly been stymied by PC makers’ cost-cutting efforts to settle on the cheaper to implement but much more limited USB as “good enough” for most users.

USB4 standard mandates USB-C ports and cables

Last year, Intel announced plans with Apple, Microsoft, HP, and chipmakers Renesas, STMicroelectronics, and Texas Instruments to define a unified USB4 standard. It would offer the same ultra-fast 40Gpbs bandwidth of Thunderbolt 3 along with improved support for tunneling USB 3.2, DisplayPort, and PCIe protocols across USB-C cables.

In addition to mandating USB-C, USB4 also requires support for the USB-PD (Power Distribution) specification for charging devices over the same cable that delivers data.

Defining USB-C as a requisite part of USB4 should help to broaden the use of the modern, omnidirectional, and more robust USB-C hardware standard for cables and ports that Apple has exclusively standardized on in its recent Macs. This is happening even as some critics have bemoaned the loss of the legacy USB-A connectors that have been in widespread use since they were first popularized by the original iMac back 1998.

Apple added USB-C to its iPad Pro and now ships its newest iPhones with a Lighting to USB-C charging cable. Apple has also shifted to USB-C across its charging adapters for MacBooks.

Thunderbolt 3 strikes again

The USB4 standard also offers the potential, but not the requirement, to support existing Thunderbolt 3 peripherals, which involves supporting some unique differences from the core definition of USB4. For the first time, that means that other companies apart from Intel could build their own silicon controllers delivering Thunderbolt 3 speeds and even compatibility without needing to buy a component from Intel.

This agreement was ideal for Apple— and was necessary for the company to deliver its new M1 Macs with support for both the refreshed new USB4 and compatibility with existing the Thunderbolt 3 devices that Mac users already have. Previous Apple Silicon chips— including the A-series SoCs used to power iPhones and iPad— never could support Thunderbolt.

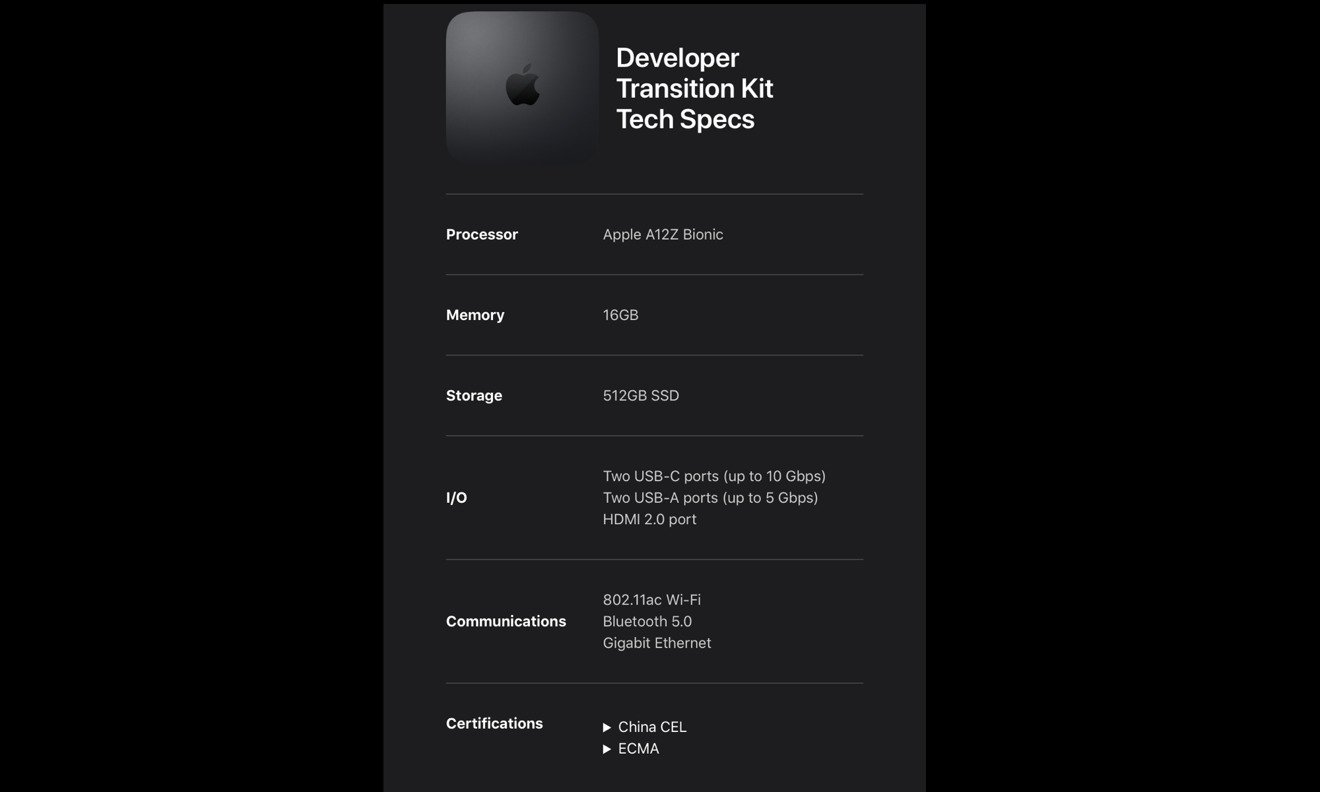

That’s why Apple’s WWDC20 Developer Transition Kit, basically a Mac mini case outfitted with an iPad Pro-class A12Z Bionic chip, could only deliver the same USB 3 support as the iPads that chip was initially designed for.

The Developer Transition Kit specs reflected a souped up A12Z iPad Pro

PC makers who wait for Intel to deliver chips for them were initially expected to gain support for USB4 early next year with Intel’s Tiger Lake processors. Some machines are already shipping, as Smith noted. This summer, Anandtech reported that the first devices supporting USB4 could ship before the end of 2020. However, there has been less urgency outside of Apple to move to USB4 because PC makers could already license Intels’ existing Thunderbolt 3 chips if they want to deliver ultra-fast connectivity.

No other PC makers have shown any ambition to develop their own custom silicon in the model of Apple’s M1, and few have been that enthusiastic about Thunderbolt. USB4 should help drive the adoption of cost-effective USB disks that can achieve Thunderbolt 3 speeds faster than the more typical 5Gbps of USB 3.x devices. That should benefit everyone, including Mac users.

Effectively, USB4 as a wide standard should help make the technology used by Thunderbolt 3 more broadly available. In supporting both existing Thunderbolt 3 devices and new devices appearing under the revised standard branded as USB4, M1 Macs will be ready for the peripherals of the future as well as the high-performance devices existing Macs can already use.